PL version below

Import Export is excited to present “Inner Edge” – a solo exhibition by Dominika Kowynia (b. 1978, Sosnowiec, PL).

Primarily a figurative oil painter, Kowynia received her MFA from the Academy of Fine Arts in Katowice in 2003. Awarded a PhD from the same academy in 2010, she continues teaching at the faculty.

In Kowynia’s canvasses echo her interests in politics, feminist theory, ecology, collective memory and trauma studies. Often drawing inspiration from personal archives, political events and contemporary literature – i.e. novels by Doris Lessing, Margaret Atwood, but also, the artist delivers a critical vision of the current time set in the context of personal inner landscapes.

“Inner Edge'' at Import Export brings together a collection of eight paintings selected by the artist. Created over the last 18 months, the works broach subjects of personal boundaries, self-worth, bodily and emotional safety – marking the artist’s indirect yet visceral response to the events and the aftermath of October 2020, when Poland’s Constitutional Tribunal introduced the near total ban on abortions in the country.

Coinciding with the exhibition at the gallery are two institutional exhibitions featuring Kowynia’s works: solo exhibition “The Second Body” at BWA Olsztyn City Gallery and group exhibition “Who will write the history of tears. Artists on Women’s Rights” at the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw (both on view until the end of March).

CHECKLIST – Inner Edge

DOMINIKA KOWYNIA CV

To celebrate the International Women’s Day, we invited Berlin-based writer Phoebe Blatton* to collaborate and engage with the new paintings by the artist. Her essay for “Inner Edge” can be found below.

* Phoebe Blatton contributes to ArtReview, Art Monthly and Frieze, among other publications, and a selection of her writing can be found at phoebeblatton.blogspot.com

______

Together with the artist, we will donate 10% from sales of this exhibition to Ocalenie Foundation, the Warsaw-based charity leading the relief efforts to refugees fleeing Russian invasion of Ukraine.

If you are interested in making an independent donation, we invite you to follow the instructions on the foundation’s website: https://ocalenie.org.pl/ .

_______

Import Export ma przyjemność zaprezentować wystawę “Krawędź wewnętrzna”, będącą pierwszą indywidualną prezentacją malarstwa Dominiki Kowyni w galerii. Urodzona w 1978 roku w Sosnowcu, Kowynia ukończyła w 2003 roku studia magisterskie na Akademii Sztuk Pięknych w Katowicach. W 2010 roku obroniła tam także doktorat, a następnie habilitację (2018), i dziś jest wykładowczynią.

Po latach poszukiwań formalnych, rozpościerających się od figuracji do abstrakcji, Kowynia rozwinęła własny, szczególny język wypowiedzi. Zbliżony do realizmu afektywnego, charakteryzuje się on wykorzystaniem szerokich płaszczyzn żywych kolorów, niekiedy zestawionych z impastowo nakładaną farbą i dramatycznymi światłocieniami. W płótnach Kowyni echem wybrzmiewają jej zainteresowania: polityka, teoria feministyczna, ekologia, pamięć zbiorowa i studia nad traumą. W płótnach Kowyni, w których punkt wyjścia stanowią często rodzinne fotografie, aktualne wydarzenia czy literatura – między innymi powieści Doris Lessing, Virginii Woolf, Margaret Atwood czy Ngozi Adichie, polityczne ukazane jest w kontekście osobistych krajobrazów wewnętrznych.

Wystawa „Krawędź wewnętrzna” skupia grupę ośmiu obrazów wybranych przez artystkę. Powstałe w przeciągu ostatnich 18 miesięcy, poruszają one tematy osobistych granic, poczucia własnej wartości, bezpieczeństwa cielesnego i emocjonalnego. Cykl 8 prac Kowyni zaprezentowanych na wystawie powstał jako trzewiowa – choć czasem zawoalowana – reakcja wobec wydarzeń i następstw października 2020, kiedy Trybunał Konstytucyjny wprowadził niemal całkowity zakaz aborcji w Polsce.

Prace Dominiki Kowyni można jednocześnie obejrzeć w BWA Olsztyn, gdzie trwa indywidualna wystawa artystki pod tytułem “Drugie ciało”, oraz jako część wystawy zbiorowej „Kto napisze historię łez. Artystki o prawach kobiet” w Muzeum Sztuki Nowoczesnej w Warszawie. Obie wystawy są dostępne do zobaczenia do końca marca.

LISTA PRAC – Krawędź Wewnętrzna

DOMINIKA KOWYNIA CV

___

Z okazji Międzynarodowego Dnia Kobiet zaprosiliśmy do współpracy berlińską pisarkę Phoebe Blatton, która twórczości Dominiki Kowyni i wystawie “Krawędź wewnętrzna” zadedykowała swój autorski esej. Zapraszamy do lektury poniżej.

Pisarka współpracuje m.in. z ArtReview, Art Monthly i Frieze, a wybór jej tekstów można znaleźć na www.phoebeblatton.blogspot.com

holding space – essay by Phoebe Blatton

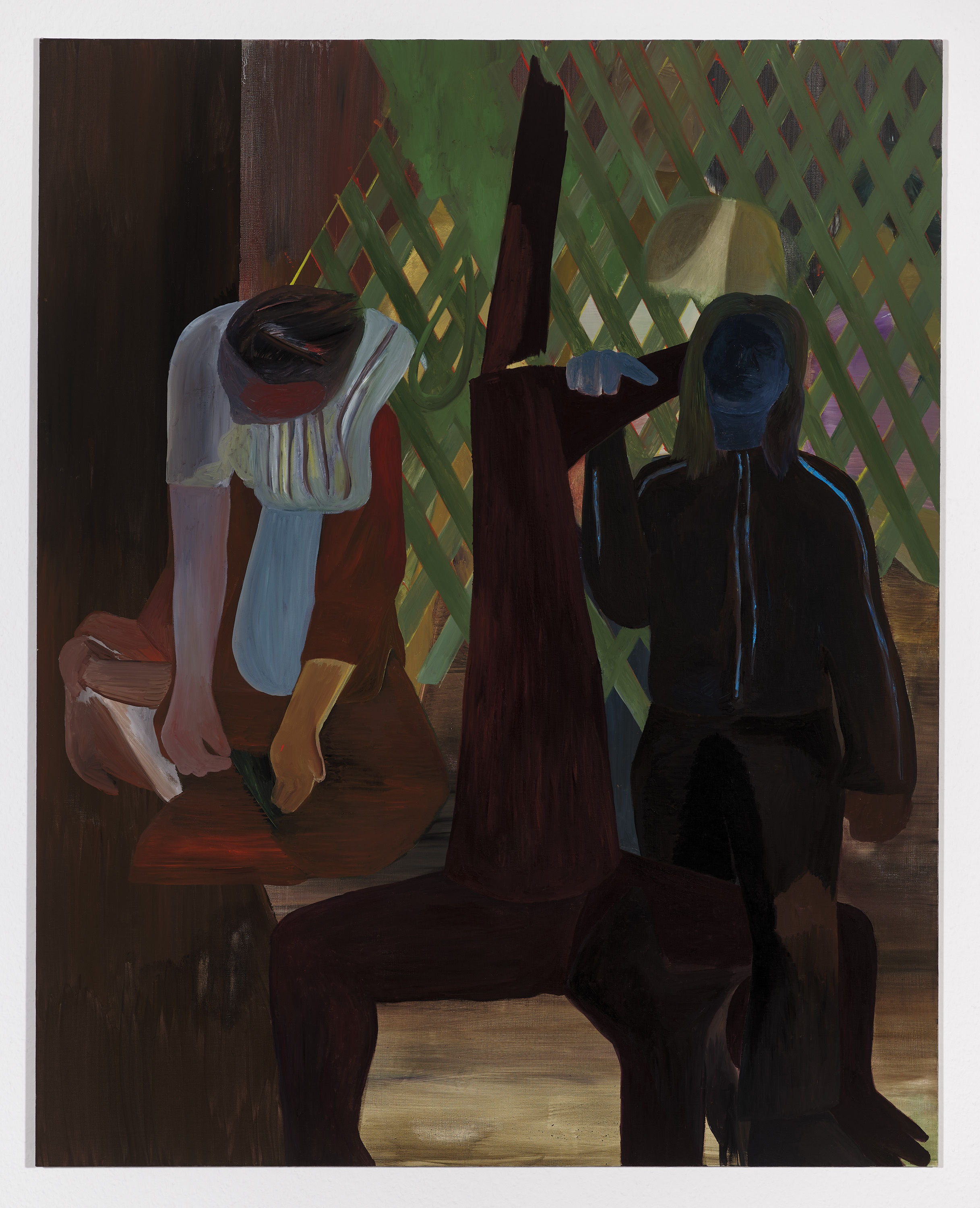

Dominika Kowynia’s exhibition, Inner Edge, at Import Export, features eight paintings that read like dreamscapes, the play of light and shadow appearing to defy an obvious source, or elements pasting across each other as though dislocated or permeable. Knowing that they’d been painted over the last eighteen months, the paintings’ sense of interiority is palpable. The composition of Głosy (Voices), ushers the viewer into this realm, but a spectral figure seems to be attempting to depart the scene, encountering the almost repellent, acidic green light of the window. My attention returns to the murky underside of the table, at which a figure, arguably the same figure, sits. In Kowynia’s paintings, light and dark can disturb in equal measure, and it is difficult to draw a distinction between night and day.

It occurred to me that a memory I had been turning over in my mind against the anxiety of the current moment, a memory that was aptly related to the experience of delirium, needed articulating to help me reach deeper into Kowynia’s world.

![Dominika Kowynia, Voices [Głosy], Oil on canvas](https://static-assets.artlogic.net/c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/ws-artlogicwebsite0516/usr/library/main/images/impex-2022-03-302252.jpg)

As a child, I used to experience painful ear infections, for which my dad had a novel treatment. Keeping his hand just above my hot, congested head, he would begin a searching, sweeping motion, bringing his thumb and fingers together in a pinch. With a quick tug, he’d fling the invisible thing that had been captured away. He would repeat this action, softly chanting a mantra in his mother-tongue of Polish: ‘Tłusta mała żabinka, tłusta mała żabinka …’, each syllable weighted like a steady drumbeat as the troublesome ‘little fat frogs’ inside my ear were caught by the leg, drawn out and thrown away. Just as the viewer will always perceive something familiar in abstraction, I experienced a kind of pareidolia in my dad’s language, hearing ‘twist’ in ‘tłusta’, which added an onomatopoeic quality to the mantra. This singular kind of witchcraft-cum-reiki, passed down to my father from his father, was so powerful, I truly felt better. As left field as it may seem, this story helps me think about Kowynia’s practice and how she aligns these works with the notion of ‘holding space’; a term from relational therapy that she encountered in Rebecca Solnit’s Hope in the Dark, written against the despair that left-wing activists experienced during the Bush administration’s invasion of Iraq.

To provide holding space means ‘being physically, mentally, and emotionally present for someone’. Painting has a symbiotic nature for the artist in this way, the canvas becoming a physical and psychological co-responder, being very much ‘present’ for the artist, as the artist is for the painting. In Kowynia’s case, this presence is often extended over months until a work is considered finished. My dad’s cure had been a kind of holding space when I was in distress, the chant creating a soundscape for recovery. My dad was no doctor (in fact, he is a painter), just as the painter can’t really call themselves a boots-on-the ground activist, but the alchemy that a caregiver or artist can create is dependent on love, which, I would suggest, can also be defined along the same lines as ‘holding space’.

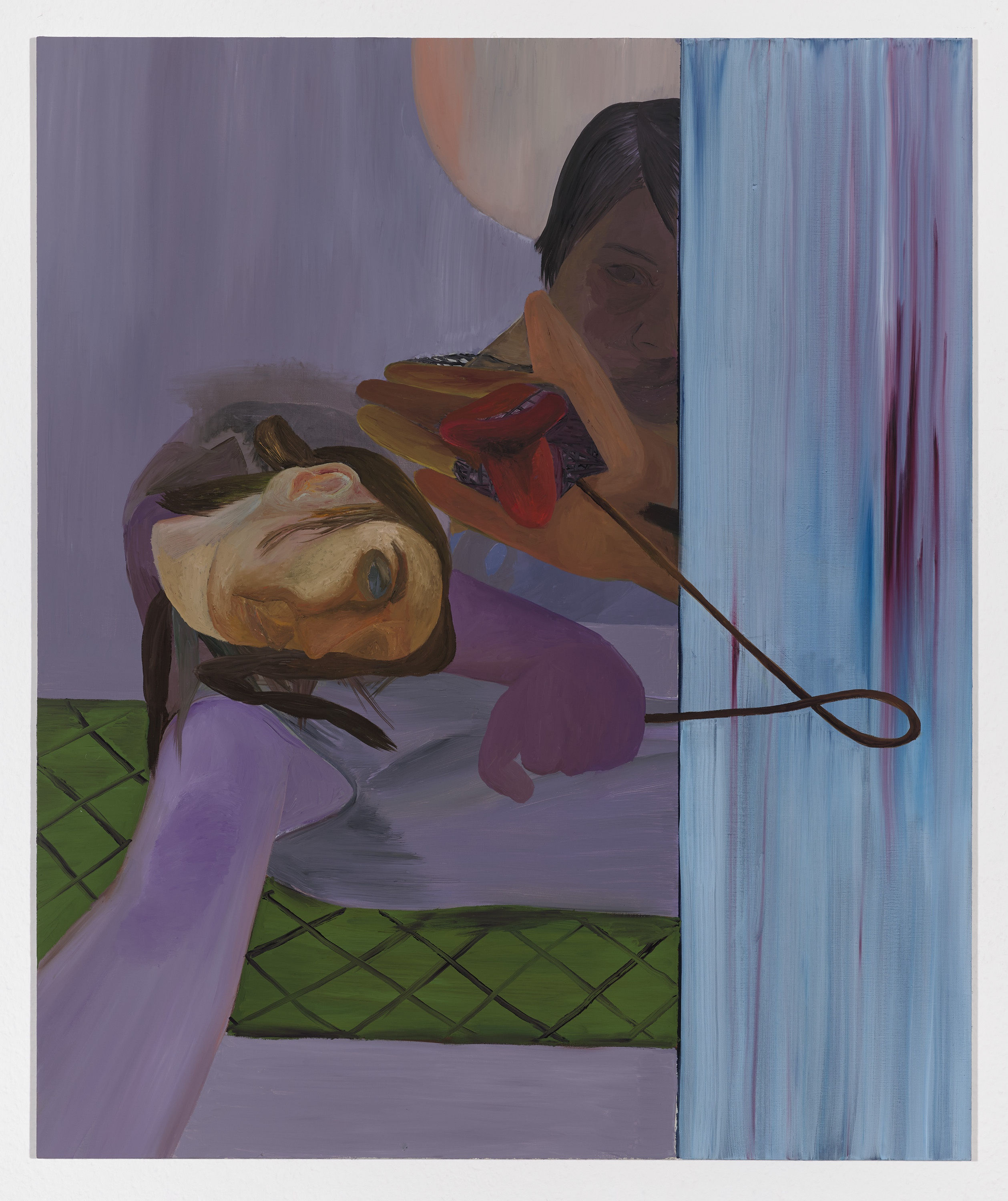

In the painting named after this concept, a figure stands over another who holds a hand toward their hidden face. Behind the figures, a monumental dark hand, recalling the Black Power salute, is unfurling, or curling up, into a fist. Ambiguously situated between the standing figure and the hand is an element that could be a ravaged flag or skewered creature. These motifs link back to Solnit’s reckoning with activist despair and are intimations of what occurred during the pandemic; a time when many governments cynically distracted from their failings by scapegoating their usual targets (and when those targets dramatically rebelled). Poland saw the intensification of anti-LGBTQ rhetoric during the 2019 parliamentary election. The returned Law & Justice party rewarded their Catholic fundamentalist base, who possess a seemingly insatiable desire to repress sex education and women’s rights, with a near-total ban on abortion that has since (at time of writing) resulted in the avoidable deaths of at least two women. This barbarous situation exists despite the extraordinary scenes of protest that erupted throughout the country in 2020/21. Kowynia’s Mówi Nie (Says No), the hospital curtain partly drawn across the scene, rings heavy with this fact. She has very consciously made these paintings ‘in the world’, committing to ‘the sole act of being present’ as she paints. In Możliwości (Possibilities) the tension that Kowynia feels as ‘a gentle person’ who nevertheless, must fight what is occurring around her, is transmitted in the contrasting figures of a woman in the historical housewifely attire of a blouse and apron, her head bowed, her hands possibly involved in invisible work or the gesture of begging (in surrender?), while to her left, gripping or breaking the fractured, bark-like element between them is a figure with loose hair, her black tracksuit zipped up to the chin in readiness for combat. With the barest touch on her shadowy face, Kowynia conveys the defiance in her expression.

Dominika Kowynia, Says No [Mówi Nie], Oil on canvas, 120 x 100 cm

Dominika Kowynia, Posibillities [Możliwości], Oil on canvas, 150 x 120 cm

Comparisons between artists are best made lightly, but echoes of Andrzej Wróblewski emerge when appreciating Kowynia’s distinctive handling of colour and the sense of ‘edge’ within her compositions. Indeed, such painters who reflected the seismic turmoil within Poland during the 20th Century, veering through expressionism, abstraction and surrealism, feel like touchstones. In Krawędź Wewnętrzna (Inner Edge), Kowynia exploits colour to convey gloom; in Skręć się (Twist yourself) she dials up contrast and a sense of confinement; in Letnio (Summer), densely painted areas are overlaid with more ghostly applications, while the red and black landscape simultaneously evokes Japanese lacquerware and the colours of the All-Poland Women's Strike movement. Hands feature prominently in the works, holding, twisting, reaching, grappling; figures are variously engaged in the action of extraction. In childhood, Kowynia was disciplined with the phrase ‘twist yourself’ (something akin to ‘Get lost!’ in English), and so the girl in Skręć się (Twist yourself) literally twists herself and hangs like a bat, subverting the telling-off by defining herself as something other, and thus free. But it is hard to look at this batgirl, tapering off into a single fibre, and not trace an umbilical line to the contorted figure of Mówi Nie (Says No), whose arm reaches towards the viewer beyond the canvas as she gives birth to something that seems only mouth, tongue and teeth, her other hand grasped around the umbilical cord that still connects her to this progeny. Like the cord that is also hinted around the totem-like figure in Letnio (Summer) or threading the figures of Głosy (Voices) together, the arm reaching out of the frame threatens to twist around the neck of the viewer. Is she flailing in desperation, or deliberately lassoing us into a confrontation with the scene?

Dominika Kowynia, Inner Edge [Krawędź Wewnętrzna], Oil on canvas, 120 x 120 cm

Dominika Kowynia, Twist Yourself [Skręć się], Oil on canvas, 150 x 130 cm

Recalling Możliwości (Possibilities), there are hints of traditional clothing in Krawędź Wewnętrzna (Inner Edge), in what could be the bright embroidery of a bodice, a red sash, a full skirt and the boots of the woman who holds a sphere aloft as she appears to expire. Does this sphere represent, as the title suggests, her ‘inner edge’, another phrase derived from psychology, which refers to the ‘internal boundary’ protecting you (and others) from yourself? In the background, as in Niosą i Karmią (Carrying and feeding), there are what looks like women at work, their obliviousness to an outside gaze reflecting the artist’s ambivalence to those women who have ‘carried and fed’ her, who ‘continue feeding me and inspire my paintings’. Though they don’t look at her (or us), in Niosą i Karmią (Carrying and feeding), Kowynia situates herself with them as the artist, recording them, but faced towards the viewer. As in Głosy (Voices), the self is split, contemplating, resting, meeting our gaze, fleeing, all at once. Kowynia’s paintings suggest that umbilical ties might never be truly severed, whether to our forebearers, our lands or our futures. But such ties can either form a noose or encircle a holding space. In any case, it is always vital to go ‘twist yourself’.